The Art of Tree Shaping with Clojure Zippers

This is a talk I did for the “Den of Clojure” meetup in Denver, Colorado. Enjoy!

Captions (subtitles) are available, and you can find the transcript below, as well as slides over here.

For comments and discussion please refer to this post on r/Clojure.

Transcript

Arne:

My name is Arne. I’m from Europe but I flew in because I met Dan in Berlin recently and he told me about this awesome meetup, so I was like, yeah, I gotta check that out. I’ve been here just long enough to get over the light headedness. Yeah, I do Clojure consulting and training. I also make Screencasts about Clojure. I don’t know if anyone’s seen Lambda Island, lambdaisland.com. You can find videos about Clojure.

Dan:

I heard there’s even an article there that maybe someone around here wrote? Yeah?

Arne:

That is true. Yeah. Den of Clojure speaker, Joanne Cheng, wrote an article about D3 and ClojureScript, which is really neat.

Dan:

Awesome.

Arne:

Yeah.

Dan:

Cool. Well, thank you for joining us all the way from Berlin.

Arne:

Thank you very much for having me.

Dan:

Yeah. Pretty cool to come down here. You’re gonna talk to us about zippers.

Arne:

Zippers, yes. Functional zippers.

Dan:

Functional zippers. It’s a fun term, isn’t it?

Arne:

Who’s used zippers before?

Dan:

Take it away.

Arne:

A couple of people, okay. All right. I’ve got a lot of slides so I’m gonna keep the pace. I’m gonna put on a timer so I’ll have a rough idea. If I really go over time, I’ll cut it short, but we’ll see how it goes.

So, yeah. Welcome to my talk, The Art of Tree Shaping with Zippers. So you already know who I am now, I’m Arne Brasseur, I’m Plexus on the Internet. I’m from Belgium, originally, a tiny country in Europe between France, Germany and the Netherlands. Beer, chocolate, waffles, fries, mussels, all the good stuff. But I’m currently living in Berlin, in Germany.

I do, like I said, Clojure consulting and training for a living, as well as this thing, Lambda Island. There’s tons of cool Screencasts on there, been going for about two and a half years, there’s 40 something episodes there. It ranges from core stuff like transducers, or small stuff like the some function, but also Datomic, reagent, re-frame, tooling, ClojureScript compiler, Integrant, you name it, there’s 40 something episodes on there now. Some of them are free, some of them you can buy, and then you can also just sign up for an all-access pass. So, yeah. That’s me.

The Agenda for today is, first, we’re just gonna look at Clojure zip from a user’s perspective. Just walk through some examples, what the API feels like, what you can do with it. Then, we’ll talk a bit more about, okay, what exactly is this whole functional zipper idea, where does it come from and why does it matter, why is it relevant? Then, we’ll look at how Clojure implements zippers. Then, finally, very briefly, I’ll touch on a couple of libraries that build on zippers, stuff that you can go from there.

The clojure.zip API. Before I can really show you examples, you need some kind of mental model of what we’re talking about when we say “zipper.” So, a zipper, also called a “loc,” or “location,” is like a two element tuple where the first one is some kind of tree-shaped data structure. It can be all kinds of things, but anything that has nodes with children. Then the second one is kind of a pointer to a specific node, like a way of focusing on a specific node. Or you can also think of it as a path in the tree to say, “Okay, now we’re dealing with this particular one.” So, as a metaphor, you can think of it as having a map with a dot saying “you are here.” The map plus the dot, that’s your zipper. With the difference that when you have the zipper you can move that dot around and make changes to your map, but we’ll get to that in a second.

The zipper API allows you to navigate in your tree. You’re looking at a specific node, and then you can say you wanna go up, down, left, right, and then when you end up at a certain location you can start making changes. When I say “making changes,” it’s Clojure, so it’s immutable, like Clojure’s own data structures, so it really just means that you get a new copy or a new version, an updated version of your zipper. Same with the navigation, it’s also in a functional way. I mean, if you’re used to how Clojure works, this should be quite natural. I’m just pointing out that when I say “replaced,” or “removed,” it’s functional still.

clojure.zip comes with Clojure itself. You don’t need to install anything extra. If you have Clojure, you have clojure.zip. You just need to require it. It’s quite typical to require it and call it “z.” Then, there’s a couple of different functions to take a data structure and turn it into a zipper to wrap it into that two element tuple.

For instance, if you have nested vectors, you can think of nested vectors as being a tree structure. So, if you say then vector-zip and you pass it a vector, you get the zipper or the loc over that vector back. So, yeah, I’m using all these terms interchangeably. We’ll look more at where the term “loc” comes from when we talk about the origin of the zipper idea.

Like I said, a nested vector can be considered a tree, a nested sequence can be considered a tree, XML documents are quite naturally a tree. So, you have an element, an element has children, and then those elements can have their children. But anything that has nodes and child nodes can be a zipper. We’ll look a bit more about how that works when we look at the Clojure implementation.

I’ll walk you through a very simple example. Here, I have a vector and I’ve turned that into a zipper. On the right-hand side, you see a visualization of what we’re looking at now. We’re looking at the vector as a tree and we’re pointing at the root node. That’s why the top node is colored blue. That blue is your dot saying you are here.

Then, you can go down, now we’re just looking at that first subvector. You can go right. You can go down again. You can go to the right-most sibling on the current level. Then, when you end up at a certain point, you can do these operations. For instance, you can append an extra child node to the current node. So now, I have appended an extra X and you see that now this node, instead of just four, five, now it has four, five X.

Then, you can go up again. Now at some point … So, all of the time … You see I’m threading this, the result of each function call is a new zipper. Now at some point you want a plain value again. You want the value of the node you’re currently looking at. That’s what you use the node function for. Given the node that you’re currently looking at that gives you the value of that node.

It’s also very common that you just wanna go all the way back to the root, all the way back to the top. You say up, up, up until you can’t go up any further, and then get the value of the complete structure. The combination of that is encapsulated in the root function.

Yes?

Participant: Is it required that only the leaf nodes have values?

Arne: Well, the only requirements that the zipper API has is that for whatever structure you give it, you can define what is a branch node and what is a leaf node, where a branch node is anything that can have children. In this case, when you’re using vector zip, it’s gonna consider anything that isn’t a vector as a leaf. But you can define that however you want, but you do need sort of a dichotomy of it’s either a branch or it’s a leaf, it can’t be both. Does that answer your question?

Participant: [This is a bit hard to understand in the recording, the participant is asking about whether branch nodes can have values, i.e. contain extra information besides the list of children. In the vector example this isn’t clear, because a vector’s value is fully determined by its children.]

Arne: Yeah. You can have extra values on that node. Say, an XML document, an element has attributes, absolutely, yeah. You don’t see that in the vector example because a vector doesn’t contain much more information besides its children, but, yes, a node can have extra information besides its children. Absolutely, yeah.

We’ll get to that now. Here’s a second example, I came up with some hypothetical XML. This is the representation of a shopping cart, which has line items and a customer. In line items, there’s two product line items, and a discount. Clojure has a set of XML parsing functions built-in. So, I’m using clojure.java.io to read that file and then Clojure XML to parse it from XML to a Clojure data structure.

Then, the result is something like this. This is how clojure.xml represents XML documents, so it uses Clojure maps and vectors where each XML element turns into a map which has a tag attributes and content, which are its children.

When you get something like this, then you can pass that to the zipper xml-zip function and you get a zipper over that XML document. This is now, yeah, it’s getting a little small here, the visualization. That top one, for instance, that’s cart and then it’s two children have line items, customers. So this is a representation of that XML that we just saw.

I can do the exact same thing. I can go down, I can go down, right, right, left-most, down. Now I can replace the node. So before it was a string node that said “chocolate” and now I’ll replace it with “luxury chocolates.” Now I go up and then I use the edit function. The edit function is like update or swap or any of these functions that you take a function that you apply to a value to get a new value. In this case, I’m gonna take the value in this node and assoc-in the attributes map a new price, because now it’s “luxury chocolates” so the price has gone up. So, before it says :price 2.5, and now it says :price 2.9. Then I’m done and I go back to the root and I get the root value.

Now you don’t write actually code like this where you just say, down, down, left, right, replace, … . You’re gonna wrap this in a function and actually check where you are and what you’re doing. But conceptually, this is what you typically do. You walk around your tree, you make changes, and then in the end you go back to the root and get the root value. That’s how zippers work.

So, you’ve seen most of the API already. I’ll just quickly run through the full API, it’s not that big. There’s a couple different ways to create zippers. We’ve seen a few of those. There’s different functions to navigate. We’ve seen all of these. There’s a bunch of functions to update. We’ve only seen a few of these, but it’s basically insert a sibling on the left, insert a sibling on the right, insert a child on the left, insert a child on the right, “edit” to apply a function to the current node value, remove a node, and replace a node with a new node.

Then, just a helper functions, which takes an existing node and a new sequence of children, and creates a new node which has all the attributes of the old node but with a new set of children. We’ll get to that again later. You’ll come across them and I’ll make a note later when we talk about the implementation, why that is interesting.

Then, finally, you can look around. Right? You end up at a certain point and you can say, what are my left siblings? What are my right siblings? What are the children of this node? You can ask for the path. This gives you a sequence of node values from the root up to your current node that you’re currently looking at. Then, you can just ask, is this a branch node or not?

Then, finally, there’s these tree functions which come together, which give you a straightforward way to do a complete walk of all the nodes in your tree. This has a depth first walk, so you start … Yeah, I’m using iterate. If you’re not familiar with iterate, it says “take that zipper and then apply the next function to it over and over and over again”, and it returns a lazy sequence of all the results.

Here I have applied it zero times, so I’m still at the root. Then, one time, and you see it starts going down to the next one, to the next one. It’s depth first, so it goes to the bottom, and then the next one, it goes left and up, left and up, until you’ve seen every single node in the tree. Then, if you go next one more time, it goes back to the root and adds a special marker to that zipper that says “this is the end point.” So now, you can use that end predicate to say that, “Okay, am I done walking? Am I done checking every single node?”

So now you know the complete zipper API in my talk here, but I still have a lot of interesting things to talk about. First of all, I’m gonna give you a couple of caveats. Now you’re gonna probably forget these, but hopefully when you actually get into the thick of it and you start banging your head against the wall, because something isn’t working the way you think it should be, then maybe at some point you will be like, “Oh, actually this is what Arne mentioned, this is the one thing that I should watch out for.”

These are - there’s no boundary checks, so don’t fall off your zipper - There’s no way back from end - zippers are not cursor I’ll go over these one by one.

No boundary checks simply means that if you go down, down, down until you get to a leaf node and you go down once more, you get nil. Up to that point all is well, but then you do one more thing and you get a NullPointerException and you need to start looking like, okay, where did that nil come from? That is how the API is designed, you know, also left, left, you go left one more time, you get a nil. It means that you can do stuff like this, (if-let [left (z/left ...)]) if I can still go left, and do something there, so it’s a fine API, but it is something to, you know, you do wanna have some checks and assertions in there to make sure that you don’t need to start chasing your nils after the fact.

The second thing I wanted to point out. So, I said, okay, when you do this complete depth first walk of your tree, you get this special end value. That end value is in a way a zipper, but not everything works on it the way that it works on regular zippers. For instance, if you try to go to the previous node, again it’s just gonna give you nil.

The main thing here, main advice here is, this end, either just treat it as a sentinel, just as a way to say, “Okay, now you’re done,” or to get the root value back. But that’s kind of it. Don’t try to do too much with that.

Then, finally, zippers are not cursors. What I mean by that is, a cursor in text points in between two characters and that means that it can be at the beginning of a line or at the end of the line or on an empty line. Whereas the zipper always points at a concrete node, which means that, for instance, you can’t have a zipper inside an empty collection and then say, “Okay, now I wanna insert something here.” Again, that’s how it works, there’s nothing wrong with that. But depending on the kind of problem you’re solving, sometimes the cursor model is much more intuitive and so you start thinking of your zipper as a cursor because the metaphor kind of matches until it doesn’t.

Here’s a little example Say, naively, I wanna take these nested vector, go two levels down. So, I’m inside the nested vector now. I wanna remove that one, remove that two and, in place of it, insert a three. What I’m hoping for is a nested vector with a three inside. Let’s see what happens. I go down, I go down, I remove this, and now I’m looking at that middle node. That might already be a little bit surprising. This is 100% by design. Again, there’s nothing wrong with that, but you do need to know how this stuff works. We’ll remove such that it removes the node at your current location, returning the loc that would have proceeded it in a depth first walk. That means, over here, if you would have called that previous, you would have ended up in that middle node, and that’s why it gives you that middle node.

If we continue our example, you remove it, you try to do an insert, and now you’re trying to insert a sibling of the root node. You can’t have a sibling if you don’t have a parent, and so it’s going to say “Exception: Insert at top.” That’s something to watch out for.

This is even more obvious when you have an example like this. I’m looking at that one, two, and then I delete it, and now I jump to that Y. Sometimes it’s a little counterintuitive.

All right, any questions so far? Yes.

Participant: Are you familiar with xpath and would zippers be useful compared to those ways of navigating the data structures?

Arne: I mean, Xpath, I’ve used Xpath a long time ago. I mean, conceptually, it’s too different from CSS selector, right? I think having these kind of selector APIs are very useful. I think they both have their uses. For instance, say, I’m doing stuff over XML, I will very often use Enlive, which gives me that selector API. It just depends what you’re doing. There are cases where the zipper model works where you really need more context or where it’s more loosely defined. Not everything can easily be captured in a path or in this kind of expression. I think for those cases, this is a really great tool in your toolbox.

Participant: You mentioned that the pointer has to point to some node. Does that mean when you create a zipper, you have to give it a root node, or do you create the tree first? Or how do you create a zipper? How do you do it?

Arne: Yeah. You need some kind of data structure for it to work on. You can give it an empty branch node of whatever kind of data structure you’re working with, so like an empty vector or an empty XML element. But you do need something like, say, you’re dealing with XML, the minimum you would have to give it is a single tag with nothing in it and then you can add stuff from there.

Participant: Okay. Create data structure first and then you create a zipper from that.

Arne: Yeah. Typically, you’ll have data structure and you use a zipper to do stuff with it, yeah. I mean, there’ll be more time for questions at the end. I just wanna make sure that this first part is more or less clear.

Okay. I’ve given you a rough mental model of the zipper, the two element tuple. Now it’s time to refine what a zipper really is. If you look at the doc string for Clojure zip, it’s a very Hickey doc string in that it makes absolute sense if you know exactly what he’s talking about. It says: “Functional hierarchical zipper, with navigation, editing, and enumeration. See Huet.”

Huet is a French guy, Gerard Huet, who published this article in 1997: “Functional Pearl, the Zipper”, where he says, “Almost every programmer has faced the problem of representing a tree together with a subtree that is the focus of attention, where that focus may move left, right, up, or down the tree. The Zipper is Huet’s nifty name for a nifty data structure, which fulfills this need. I wish I had known of it when I faced this task because the solution I came up with was not quite so efficient or elegant as the Zipper.” It’s a pretty cool article. It uses OCaml, that’s probably the biggest hurdle to reading it. But I remember reading it a couple of years ago, it’s a fun read. I recommend it.

Huet defines two types of data structures. The first one is the path. He says, “A path is like a zipper,” and in this case, he’s talking about an actual zipper, like off a hoodie or a jacket. “A path is like a zipper, allowing one to rip the tree structure down to a certain location. It contains its list L of left siblings, its father path P, and its list of R of right siblings. It’s a recursive definition, right? Because it contains a sequence of nodes, then a pointer to the previous parent, its own parents, and then a sequence of other nodes, the left and the right. There’s also a special value top, which means that we don’t have a parent path because we’re looking at the top of the structure, so that’s a special marker.

Then, “A location in the tree addresses a subtree, together with its path. This two element tuple, which is the current node with the path, which is the path we just defined. You just see where that terminology loc or location comes from. That’s from the original article.

Here I have a different visualization. In these visualization, there’s two types of nodes: there’s the diamond-shaped ones, which are the zippers or the paths; and the round ones are regular nodes. When I have my zipper over my XML document, it’s looking at the root node, so that’s the cart, and it has that marker that says, “okay, we’re at the top.”

Now, when I go down, now the thing I’m holding is the zipper, which is looking at line items with a parent, which is the previous zipper we had, and then left and right siblings. Then, I can go down again and now I’m looking at that product inside the line items, inside the cart. What you already see here is that the tree has been turned upside down, right? Before, we had the cart at the top and now we have the cart at the bottom. The thing that we’re holding onto is the place where we’re focusing on, the node where we ended up at.

The reason that that’s cool is that, say, I go right from here, so that means that I’m gonna shuffle left, right siblings and current node, those three pieces of information are gonna change, but the parent path and anything down from there remains unchanged. So I can start doing these local operations and not care about anything that’s above me in the tree. I hope that makes sense, these spatial metaphors.

We’ll look at Clojure’s implementation later and maybe then it’ll make more sense. So, yeah, it’s a generic way of prying a nested data structure open so that you can locally make changes and then afterwards you put it back together again.

I go down again. Now I’m gonna do the same stuff that I did before. I have this chocolate node and I’m going to replace it with the string luxury chocolate. Now the zipper has turned red, which means that it has a flag set on it, which says that it has changed. Because as we said before the parent and chain of parent paths doesn’t change when you do an operation like this, which means that that product node still has the old value.

Only when we start going up again does clojure.zip rebuild those nodes. So now product has changed because now it contains a new string. Now line item has changed because it contains a new product. Finally, we’re back at the cart. This is maybe the most confusing thing about the whole thing, but again it will probably become more clear when we get to the implementation. Does it make sense? Shall I walk through it again? Okay. I’ll keep going.

Here we are at the Clojure implementation. These vector-zip, xml-zip, seq-zip, in the end they all call the zipper function. This is the main way to create a zipper, to create a loc, and it takes four pieces of information. The first three are functions and the last one is your actual data structure, the root of your tree. Those first three functions are a way to tell Clojure how your data structure works, what kind of data structure you’re dealing with. You need to be able to answer two questions and do one operation. You need to be able to have a node an answer, is it the branch node or not? Can it have children or not? When you have a node you need to be able to say, “Give me a sequence of all the children of this node.” Then, finally, you need to be able to do that make node thing where you have a node and a new set of children and you get a new node which has all attributes of the old nodes but with the new children.

If you look at the implementation of zipper, this is it. You see that two element vector in there. Right? In returns a vector with that root and with the nil, which is what Clojure uses as its marker to say we’re at the top. Right? The path is nil, there’s no parent path because were at the top.

The other thing to notice here is that it then attaches a bunch of metadata to that vector. So these functions that you passed in there got stored on that two-element vector as metadata. This is pretty neat. It’s a neat trick and I haven’t seen it in many other places. So, yeah.

Now, if you look at vector-zip, vector is just calls zipper, in the case of a vector-zip, a root is a branch node if it’s a vector, otherwise we’ll consider it a child node. Seq just gives the stuff inside the of vector. Then, the make node function, mostly just calls back on the children. In this case, it also just make sure it preserves metadata.

So far it’s fairly straightforward. If you look at the implementation of the actual clojure.zip/branch function, clojure.zip/children, clojure.zip/make-node, they look up those specific functions on the metadata and call those. This is a pretty neat way of doing polymorphism. Clojure has protocols, Clojure has multimethods, which are all different ways of dispatching to different implementations based on the specific value that you’re looking at. But this is yet another way of doing it.

Vector-zip, on that zipper you’ll see that all it really does is just wrap it in a vector and then add a nil. If you look at the metadata, you’ll see those functions there. So, it’s kind of nothing under the covers. It’s fairly straightforward once you know what’s going on.

Participant: I just wanna butt in for a second and say, “Wow, that’s really cool.” Yeah.

Arne:

So, even if you never used zippers, maybe you end up using this trick. So now, we can actually start looking at the values return from these function calls. Now I’m going to walk through that first example again with the vector-zip. After turning it into a zipper, it’s just this two-element vector. And then you go down and so now you see that the node we’re looking is the node [1 2], and the parent path, or the path at the moment has this left siblings, right siblings and a parent path, which is currently nil, which is, you know, because the parent of the node we’re looking at is the root.

Then, the Clojure also stores a sequence of parent nodes, which would use this to reconstitute, to rebuild the values as you go back up again. You can already see if I go left or right here, that left and right and the current node changes, but everything else stays the same. Now I go down one more level and you start seeing this linked structure. We’re looking at the tree now. It has left and right siblings and it has a parent path, which is the one we just had. Right?

Here we have left one, two, P nodes, P path nil, R nil, that’s inside there now, this is the parent path of the new path. Again, you know, we can go left and right and all it needs to do is change those siblings. Everything else stays the same way.

Now, append a child, it’s got an extra marker at the bottom. It’s changed now. But you see that X is now in the node that we’re looking at. But if you look at the parent node, that X isn’t there. Not yet, right? Clojure has been able to make this local change. That’s one of the benefits, the efficiency benefits of zippers that you can go deep into your structure, make a bunch of changes, and then only pay the price of rebuilding your path up to the root when you zip back up. We’ll do that now. Once you start going up, you can see that it starts building up those values again.

I’m actually doing better on time. Then I guess I really flew through this, slide 100. Okay. Two more libraries I wanna at least mention. One is fastzip. Fastzip is really just what it says on the tin, it’s faster zipper. The Clojure implementation with the vectors and the metadata, it’s super cool, it’s also nice that you can just inspect it, that it’s just the vector and you can look at those values. I do typically developed with Clojure.zip, but then when you wanna ship this in production and you wanna get those extra cycles out, you just swap out clojure.zip for fastzip. It’s absolutely the same API but it uses deftype under the hood so it really gives you this high-speed like native dispatch.

The only thing to watch out for is that you don’t rely on implementation details. Now you all know that a clojure.zip a two element vector, but if you start relying and, like for instance, destructure that vector, yeah, that’s not gonna work with fastzip. But as long as you stick to just the functions in Clojure.zip, it should work 100% the same Clojure. Clojure and ClojureScript, by the way, all of these are cross-platform.

Then, the final thing I wanna mention is rewrite-clj because this is one of the libraries that built on top zippers. In this case, in particular, it gives you a zipper over a Clojure syntax tree. So what rewrite-clj does is it parses Clojure source code, turns it into a syntax tree that preserves formatting and white space. You can process that, do stuff with it, make modifications without messing up people’s formatting. So, a lot of tools use this, you might’ve come across clj-format, zprint, lein-ancient, refactor-nrepl, mutant mutation testing, all of these use rewrite-clj under the hood.

Rewrite-clj has its own .zip name space, which largely as API corresponds with clojure.zip. For instance, in rewrite-clj, you go next or you go right, it’s going to skip over white space nodes, which is most of the time what you want. So you can deal with that AST and ignore the white space, but it is still there, when you build it up, you turn it back into text. The formatting is still there.

You also get some extra goodies, some extra functions that are particular to dealing with source code. So this is pretty nice library. Because, yeah, people keep asking me, “Okay, yeah. You know, I’ve looked at these zippers, but what do you use them for?” So this is, for instance, one real use case that I used them for not too long ago. A project that’s a year or two old, we started out with a certain namespace organizations and halfway through decided to have a bit more of a thought out namespace organization with proper, you know, reverse domain name and all of that stuff.

So, we had about 50% of our code using the old scheme and the new scheme. At a certain point we wanted to clean that all up. But at the same time it had to all happen as a big bang thing because you don’t want to block everyone who’s working on this. The solution was to write a script, which goes over to complete code base, updates or require statements, updates of namespaced keywords, all that kind of stuff so that we can find an opportune moment to merge as much as possible, run this once, get it over with.

This is one function in there, you see there’s a loop recur, which takes the input zipper and then just goes next, next, next. It goes over the complete source code until it’s either at the end, then it stops. Or if it’s looking at a list and the first element in that list is a :require keyword. In that case, it goes down into the list and passes the zipper to another function which will do the actual updating of the requires. This is one example of what zippers in the real world might look like.

This is my last slide. I didn’t go as much over time as I thought I would do. One more thing that I used zippers for recently, so I was working on a project which does a Jupiter notebook kind of interface. So, these are these environments in a web browser where you can evaluate code, and so we had streaming output from the server to the client. There’s two things that are tricky with that because you need to emulate a repl like a terminal. You need to deal with ANSI escape codes, but you also need to deal with carriage returns.

Like, if you have, for instance, a progress bar, you know, that would work in a terminal, then you need to emulate that in your HTML. If you’ve come across a carriage return, go back to the beginning of the line where the beginning of the line, in this case, is actually a bunch of spans that are encoding your color stuff. There I extensively used zippers to navigate back, “Okay, where is actually the beginning of the line, split this up.” So, that was another use case.

Yeah. That’s all I have. But I am here for questions. Questions. Yes.

Participant:

I kind of wanna ask about possible extensions to the zipper idea. I think it’s cool. What if you wanted a zipper except with two pointers? Or what if you wanted a zipper that instead of a tree data structures worked on directed acyclic graph or general graphs. Do you have any ideas?

Arne:

That’s an interesting research topic. I think the reason that zippers came to be is the idea of … actually I have one more slide here. I briefly mentioned this in passing, but it’s the idea of … Here are two different ways of doing the same thing, right? The bottom one, I’m just using Clojure’s assoc-in to replace a value deep inside a tree, whereas the top one, I’m doing the same thing with zippers. In this case, I mean, both do the exact same thing. But if you have a bunch of those assoc-in, so each time Clojure needs to go from the top to the bottom, make that change, and so you end up with a data structure on the right, which we use as a loc on the left, but anything from, you know, your position where you make the change up to the root, those will all be new nodes.

If you do a bunch of updates every single time, you’re rebuilding that path from your current position to the root. That’s really why zippers shine, because you can defer that cost as much as possible. So, in a more general graph structure, I think … I don’t know. I can’t answer off the top of my head if you can do the same. I mean, I guess, if your directed acyclic graph still has the concept of a root that you considered a root because you still wanna do it in kind of a functional way, then I guess you can do something similar.

Having to two pointers at the same time, I think this is going to start getting very, very tricky. You’re going to have to do a lot of bookkeeping and I don’t know if it still worth it … I guess, it also like to see if there’s a use case for it. It might be possible. Yeah.

Participant: Would you say that the benefits of using zippers scale with the number of changes that you need to make deep inside of some nested structure?

Arne:

I mean, that’s one of the benefits of zippers, is in the performance gain. So, yes, performance-wise you’re gonna get more bang for your buck, the more that you can cluster operations together, navigate to a certain position, do your changes there and then all these zip at once. But I think the other thing, people that use zippers, I don’t think performance is often the first reason, I think the main reason is that there’s certain problems where there’s navigation API is just very elegant. That’s probably the main reason that people choose zippers.

All right. Well, I’ll be here. I’m happy to chat later.

Dan: Thank you.

Arne: Thank you all very much.

Dan: That’s great. Just because I don’t think we were streaming then, Arne, how do I pronounce your name, I’m sorry?

Arne: Arne.

Dan: Arne, okay.

Arne: Arne.

Dan: You do freelance Clojure consulting. Are you looking for more clients?

Arne: Actually, not right now. I mean, I’m always happy to talk, there might be interesting stuff, especially when it comes to training with some people in Berlin.

Dan: You could still … maybe put on your wait list?

Arne:

Absolutely. But I actually just recently said goodbye to a consulting gig because I wanna spend some time on Lambda Island. I got some open source work that I’m committed to now with Clojurists Together. I’m also organizing a conference next year. It might be a little bit far from most of you. It’s gonna be in Belgium, Heart of Clojure, but it’s going to be an absolutely kick ass conference early August. I’m gonna be busy the next year, is what I’m saying.

Dan:

I’m going to be out in Belgium speaking in a conference in two weeks. Can you maybe schedule it for them? That’s great. I’ve never been to Belgium, so I’ll check it out. I’ll pre-scout it for next year’s Clojure conference.

Arne:

Yeah, yeah. That’d be awesome.

Dan:

That’s great. Cool. Well, thank you for speaking for us and I appreciate your help.

More blog posts

A Conjure Piglet Client

by Laurence Chen

“Laurence, are you interested in Piglet? Do you want to help develop Piglet?” Arne asked me. Piglet is the new language he recently released, of course, another Lisp.

“Sure, where should I start?” I replied.

The Hidden Lessons in a re-frame App

by Laurence Chen

I took over a web application whose frontend was built with re-frame, and not long after I started working on it, I felt a bit of discomfort. So, I decided to investigate the source of that discomfort. And my first suspect was re-frame.

The reason I had this suspicion was mainly because in the frontend stack most commonly used at Gaiwan, we usually only use Reagent.

On Cognitive Alignment

by Laurence Chen

There was once a time when a client asked me to add a rate limit to an HTTP API. I quickly identified three similar options, all of which could apply rate limiting via Ring middleware:

- https://github.com/liwp/ring-congestion

- https://github.com/killme2008/clj-rate-limiter

- https://codeberg.org/valpackett/ring-ratelimit

Beyond the If Pattern

by Laurence Chen

In my work at Gaiwan, there was a piece of code with poor quality that always felt like a thorn in my side. For a long time, I couldn’t come up with a better way to handle it.

The code was a Nested If. Each step-* is a side-effect operation, and each handler records a log.

On Interactive Development

by Laurence Chen

When I was a child, my sister caught chickenpox. Instead of isolating us, our parents let us continue playing together, and I ended up getting infected too. My father said, “It’s better to get chickenpox now—it won’t hurt you. Children aren’t just miniature adults.” This saying comes from pediatric medicine. While children may resemble adults on the outside, their internal physiology is fundamentally different. Some illnesses are mild for children but can hit adults much harder—chickenpox being a prime example.

I often think of this phrase, especially when reflecting on Clojure’s interactive development model: interactive development feels natural and smooth in small systems, but without deliberate effort, it often breaks down as the system grows. Just as children and adults must be treated differently, small and large systems have fundamentally different needs and designs when it comes to interactive capabilities.

Learning Fennel from Scratch to Develop Neovim Plugins

by Laurence Chen

As a Neovim user writing Clojure, I often watch my colleagues modifying Elisp to create plugins—for example, setting a shortcut key to convert Hiccup-formatted data in the editor into HTML. My feeling is quite complex. On one hand, I just can’t stand Emacs; I’ve tried two or three times, but I could not learn it well. On the other hand, if developing Neovim plugins means choosing between Lua and VimScript, neither of those options excites me. Despite these challenges, I envy those who can extend their editor using Lisp.

Wouldn’t it be great if there were a Lisp I could use to develop my own Neovim plugins? One day, I discovered Fennel, which compiles to Lua. Great! Now, Neovim actually has a Lisp option. But then came the real challenge—getting started with Fennel and Neovim development was much harder than I expected.

On Inspectability

by Laurence Chen

At the beginning of 2025, I took over a client project at Gaiwan. It was a legacy code maintenance project that used re-frame. While familiarizing myself with the codebase, I also began fixing the bugs the client had asked me to address. This process was anything but easy, which led me to reflect on what makes an effective approach to taking over legacy code.

I have yet to reach a conclusion on the general approach to inheriting legacy code. However, when it comes to taking over a front-end project built with re-frame, I do have a clear answer: install re-frame-10x, because it significantly improves the system’s inspectability.

On Extensibility

by Laurence Chen

For a long time, I had a misunderstanding about Clojure: I always thought that the extensibility Clojure provides was just about macros. Not only that, but many articles I read about Lisp emphasized how Lisp’s macros were far more advanced than those in other languages while also extolling the benefits of macros—how useful it is for a language to be extensible. However, what deeply puzzled me was that the Clojure community takes a conservative approach to using macros. Did this mean that Clojure was less extensible than other Lisp languages?

Later, I realized that my misunderstanding had two aspects:

Ornament

by Laurence Chen

Well done on the Compass app. I really like how fast it is (while retaining data consistently which is hugely undervalued these days). I’m not just being polite, I really like it.

by Malcolm Sparks

Before the Heart of Clojure event, one of the projects we spent a considerable amount of time preparing was Compass, and it’s open-source. This means that if you or your organization is planning a conference, you can use it.

The Admin Process

by Laurence Chen

My friend Karen joined an online community of product managers and took on the task of managing a mentor-mentee matchmaking system. She has years of experience as a product manager but lacks a background in software development. Driven by her strong passion for the community, she managed to develop a Python version of the mentor-mentee matching system using ChatGPT. Of course, the story isn’t that simple. The turning point came when she was stuck, no matter how she phrased her questions to ChatGPT, and she came to me for help.

Her stumbling block was this: she was asking ChatGPT top-down questions, so ChatGPT, using probabilities and statistics, generated high-level sequential logic code, essentially the policy part. This generated code would then need to call underlying library functions, the mechanism part, to perform bipartite matching calculations. This is where ChatGPT got stuck. For such tasks, even humans sometimes have to write some glue code to handle the impedance mismatch between policy code and mechanism code, so it was expected that ChatGPT would hit a wall.

Announcing our Clojurists Together Plans

By Alys Brooks

In case you haven’t been hanging out in our Discord or Slack channel or following Clojurists Together news, we’ve been accepted into the latest round of Clojurists Together! Many thanks to Clojurists Together and the backers who provide their budget. We’re also using OpenCollective funds to match our Clojurists Together grant—many thanks to our sponsors on OpenCollective!

You may have heard some updates from fellow awardees already—we opted for a delayed start and have been gearing up to make the most of our funds over the next six months.

The REPL is Not Enough

By Alys Brooks

The usual pitch for Clojure typically has a couple ingredients, and a key one is the REPL. Unfortunately, it’s not always clear on what ‘REPL’ means. Sometimes the would-be Clojure advocate breaks down what the letters mean—R for read, E for eval, P for print, and L for loop—and how the different stages connect to the other Lispy traits of Clojure, at least. However, even a thorough understanding of the mechanics of the REPL fails to capture what we’re usually getting at: The promise of interactive development.

To explore why this is great, let’s build it up from (mostly) older and more familiar languages. If you’re new to Clojure, this eases you in. If Clojure’s one of your first languages, hopefully it gives you some appreciation of where it came from.

Setting up M1 Mac for Clojure development

By Mitesh (@oxalorg)

I recently bought an M1 Macbook Air with 16 GB RAM. Below is a log of how and what I downloaded on my machine for a full stack Clojure development experience.

The M1 is an ARM chip and thus the software which runs on it must be compatible with the ARM instruction set instead of the x86 instruction set.

Making Lambda Island Free

Six years after launching Lambda Island we’ve decided to flip the switch and make all content free. That’s right, all premium video content is now free for anyone to enjoy. Go learn about Reagent and re-frame, Ring and Compojure, or Clojure Fundamentals.

If you currently have an active subscription then it will be automatically cancelled in the coming days. You will no longer be charged. No further action is necessary.

Lambda Island is how the Gaiwan Team gives back to the Clojure community. We have released over thirty different open source projects, we write articles on our blog, post videos on our YouTube channel, we moderate the Lambda Island discord community, and provide a home for the ClojureVerse forum.

What Is Behind Clojure Error Messages?

by Ariel Alexi and Arne Brasseur

Have you ever looked at your REPL and asked yourself “What am I supposed to understand from this?”. This is not just a junior thought, but one also common to more advanced programmers. What makes it hard is that Clojure error messages are not very informative. This is why a lot of work was put into improving these error messages.

The errors seem a bit strange at first, but you can get used to them and develop a sense of where to look. Then, handling errors will be much less difficult.

Improve your code by separating mechanism from policy

by Arne Brasseur

Years ago when I was still a programming baby, I read about a concept, a way of thinking about code, and it has greatly influenced how I think about code to this day. I’ve found it tremendously helpful when thinking about API design, or how to compose and layer systems.

Unfortunately I’ve found it hard at times to explain succinctly what I mean. I’ve also realized that I’ve built up my own mental framework around this concept that goes I think beyond the original formulation. So, in the hope of inspiring someone else, to maybe elicit some interesting discussion, and also just so that I have a convenient place on the web to link to, here’s my take on “policy” vs “mechanism”.

How to control the metacognition process of programming?

by Laurence Chen

There is a famous quote: Programming is thinking, not typing. After doing this job long enough, sometimes, I feel I am doing too much typing. No matter whether humans are thinking or typing, they use their brains, so I believe the word “typing” is a metaphor: typing refers to the kind of activities that we are doing unconsciously, doing through our muscle memory, not through our deliberate attention. Many of us, with enough experience, use quite a lot of muscle memory. On the other hand, do we use enough thinking when we need to?

We, humans, make a lot of decisions in our daily life: a decision like buying a car, or a decision like naming a function. Evolution makes us become the kind of animal that we can delegate certain parts of decisions down to our subconscious minds, which we may refer to as the background process in our brain. Therefore, we can focus our mind on something that matters. Here is the problem: what if the subconscious mind is not doing a good job? Most of the time, it is not a big deal, and escalating the issue back to foreground thinking can solve it. For example, when you press <localleader> e e to evaluate a form, but mistakenly evaluating the wrong form. You detect that, then you use your foreground thinking to decide what to do next. However, sometimes, when you know that the subconscious mind can not handle the job well before you begin the job, what can you do to prevent your subconscious mind from taking over control? Do we have any mechanism similar to the linux command fg, which can bring a process from background to foreground?

Unboxing the JDK

By Alys Brooks

It’s easy to forget the Java Development Kit is, in fact, a kit. Many Clojure

developers, myself included, rarely work with commands like java directly,

instead using lein, boot, or clojure. Often we don’t even use the Java

standard library directly in favor of idiomatic wrappers.

There are a lot of advantages to staying in the Clojure level. Often, Clojure-specific tools ergonomically support common practices like live-reloading, understand Clojure data structures, and can tuck away some of the intermediate layers of Clojure itself that aren’t a part of your application.

Lambda Island Open Source Update January 2022

By Alys Brooks

Community contributors and Lambda Island team members have been busy working on new projects and improving existing ones.

If you want to join in, check out our blog post calling for contributions, or jump right in to our first issues list.

Making nREPL and CIDER More Dynamic (part 2)

By Arne Brasseur

In part 1 I set the stage with a summary of what nREPL is and how it works, how editor-specific tooling like CIDER for Emacs extends nREPL through middleware, and how that can cause issues and pose challenges for users. Today we’ll finally get to the “dynamic” part, and how it can help solve some of these issues.

To sum up again what we are dealing with: depending on the particulars of the

nREPL client (i.e. the specific editor you are using, or the presence of

specific tooling like refactor-clj), or of the project (shadow-cljs vs vanilla

cljs), certain nREPL middleware needs to present for things to function as they

should. When starting the nREPL server you typically supply it with a list of

middlewares to use. This is what plug-and-play “jack-in” commands do behind the

scenes. For nREPL to be able to load and use those middlewares they need to be

present on the classpath, in other words, they need to be declared as

dependencies. This is the second part that jack-in takes care of.

Making nREPL and CIDER More Dynamic (part 1)

This first part is a recap about nREPL, nREPL middleware, and some of the issues and challenges they pose. We’ll break up the problem and look at solutions in part 2.

The REPL is a Clojurists quintessential tool, it’s what we use to do Interactive Development, the hallmark of the LISP style of development.

In Interactive Development (more commonly but somewhat imprecisely referred to as REPL-driven development), the programmer’s editor has a direct connection with the running application process. This allows evaluating pieces of code in the context of a running program, directly from where the code is written (and so not in some separate “REPL place”), inspecting and manipulating the innards of the process. This is helped along by the dynamic nature of Clojure in which any var can be redefined at any point, allowing for quick incremental and iterative experimentation and development.

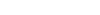

The Obstacles of Effective Debugging

by Laurence Chen

Have you ever had one of the following experiences before?

The Classpath is a Lie

by Arne Brasseur

A key concept when working with Clojure is “the classpath”, a concept which we

inherit from Clojure’s host language Java. It’s a sequence of paths that Clojure

(or Java) checks when looking for a Clojure source file (.clj), a Java Class

file (.class), or other resources. So it’s a lookup path, conceptually similar

to the PATH in your shell, or the “library path” in other dynamic languages.

The classpath gets set when starting the JVM by using the -cp (or

-classpath) command line flag.

A Tale of Three Clojures

By Alys Brooks

Recently, I was helping a coworker debug an issue with loading a Clojure

dependency from a Git repository. (If you don’t know you can do this; it’s very

handy. Here’s a

guide.) I realized that there were really two Clojures at play: the Clojure that

clojure was running to generate the classpath and the Clojure that was used by

the actual Clojure program.

Taking a step back, there are really three things we might mean when we say “Clojure”:

Launching the Lambda Island Redesign

It’s finally live! A gorgeous, in-depth redesign of the Lambda Island website. After months of hard work we soft-launched earlier this week. Today we want to tell you a little more about the project, the whys and the hows, and to invite you to check it out. And when you’re done do come tell us what you think on our Discord.

We already told you in a previous post how Lambda Island and Gaiwan are changing. In a short amount of time we went from a one man endeavor to a team of six, drastically changing what we are able to take on and pull off.

Lambda Island Open Source Update July 2021

By Alys Brooks

It’s been a while since our last update! Community contributors and Lambda Island team members have been busy working on new projects and improving existing ones. We’re trying to strike a balance between venturing into new territory while ensuring existing projects continue to improve.

If you want to join in, check out our blog post calling for contributions, or jump right in to our first issues list.

Lambda Island is Changing

Last month marked the five year anniversary of Lambda Island. Five years since I quit my job, built a video platform, and figured out how to put together tutorial videos. It’s been quite a ride. All this time I’ve been fortunate to be part of the Clojure community, to watch it grow and evolve, and to help individuals and companies to navigate these waters.

I learned some hard lessons along the way. Like how hard it is to bootstrap an educational content business catering to a niche audience, or how lonely and stressful it can be in business to go it alone.

And with these lessons came changes. I started doing more consulting work again. To some extent it was a necessity, but it also provided me with an opportunity to get involved with many Clojure projects out there in the wild. To work with talented individuals, to learn what amazing things people were doing, and to help shape these companies, products, and the greater narrative around Clojure as a technology and community.

Why are Clojure beginners just like vegans searching for good cheese?

By Ariel Alexi

Have you ever wondered what to do if you love cheese but you want to be a vegan and how this affects you when you learn Clojure?

This was my question too. I love cheese, but I wanted to find a good vegan cheese replacement for my breakfast sandwich. This wasn’t a fun journey, all the vegan cheese substitutes weren’t like the real deal! After a talk with one of my vegan friends, he told me that my point of view over cheese replacement in the sandwich was wrong. Instead of searching for a good and tasty vegan cheese replacement, just replace it with an avocado. Avocado is a good replacement for your morning sandwich without the compromising that you would do with tasteless vegan cheese substitutes.

The beginner's way

By Ariel Alexi

An OOP developer finding her way in the functional world, what could go wrong?

So why Clojure?

Call for Contributions to Lambda Island Open Source

By Alys Brooks

We’re always excited when someone new contributes a fix, test, documentation update, or even a major new feature to our open source projects. If you’re new to programming, open source projects are a great way to get experience working on a larger project. If you’re not so new, they can be an opportunity to try a new technology or work on a kind of software you usually don’t get a chance to. Either way, it’s rewarding to help out your fellow users or developers—these issues are for Kaocha, one of the most popular and advanced Clojure test runners.

But open source can also be intimidating. If you haven’t been sure where to start, then this post is for you! We’ve outlined the process step by step, and we’re here to support you every step of the way.

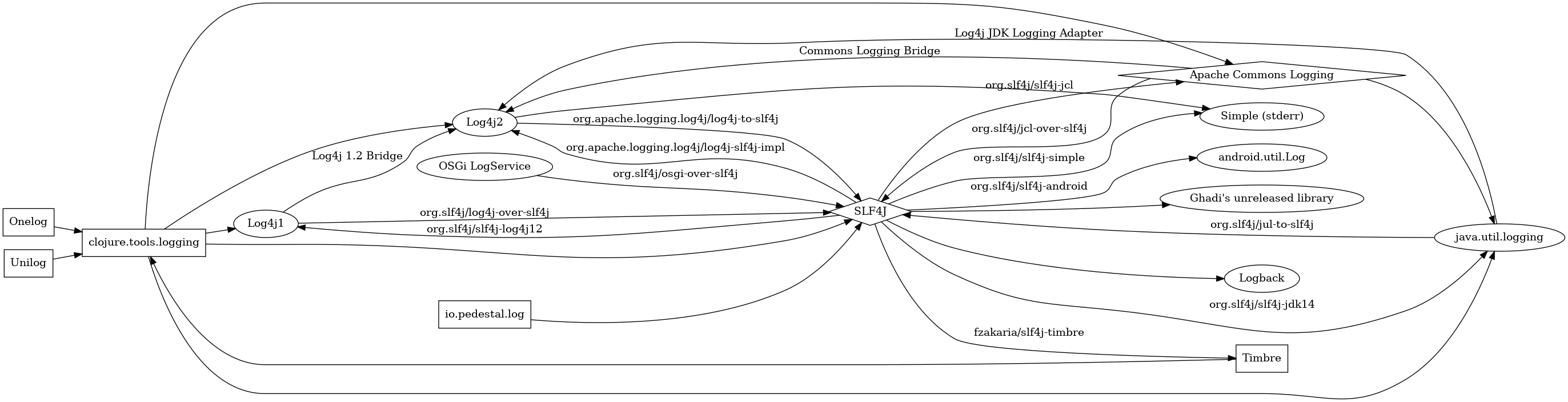

Logging in Practice with Glögi and Pedestal.log

In an earlier post I tried to map out the Clojure/Java logging landscape a bit, so people can make an informed choice about how to set up logging for their application. There are several solutions out there with different trade-offs, and recently both Timbre and mulog have had some new releases. However until further notice the default logging setup in the “Lambda Island Stack” remains pedestal.log on the backend, and Glögi at the front.

This blog post is a bit of practical advice on how to make good use of logging, with the focus on these two libraries, which both provide the same API, just for a different platform.

This API consists of a number of macros corresponding with the different log levels, which all take key-value pairs as arguments.

Well Behaved Command Line Tools

Yesterday Vlaaad wrote a pretty cool blog post titled Alternative to tools.cli

in 10 lines of code.

It’s a great read and a very cool hack. It uses read-string to parse command

line arguments, resolves symbols, and invokes the first symbol/function, passing

in the rest of the parsed arguments. In other words: it’s the most

straightforward way to translate a command line invocation into a Clojure

function call.

The benefits are illustrated well in the post. It removes all possible friction. Want to add a new subcommand? Just add a function. Adding CLI arguments and options equals adding arguments and options to said function.

It’s actually not too different from what people do in shell scripts sometimes.

Logging in Clojure: Making Sense of the Mess

You may also like Dates in Clojure: Making Sense of the Mess

Logging seems like a simple enough concept. It’s basically println with a

couple of extra smarts. And yet it can be oh so confounding. Even when you

literally do not care a sigle bit about logging you may still be sent down a

rabbit hole because of warnings of things that are or aren’t on the classpath.

What even is a classpath?

Lambda Island Open Source Update May 2020

Felipe and I have been busy again, read all about what we’ve been up to in this month’s Lambda Island Open Source update.

We currently have two major projects we are working to get out: Regal and Kaocha-cljs2. They are both still a work in progress, but we’ve again made some good progress this month. Regal is not officially out yet but is at the stage where people can safely start incorporating it into their projects. Kaocha-cljs2 is a big undertaking, but we’re splitting this work into smaller self-contained pieces, and two of those saw their first release this month: Chui and Funnel.

Regal

Lambda Island Open Source Update April 2020

With people across the globe isolating themselves it feels sometimes like time is standing still, but looking back it’s been a busy month again for the folks here at Lambda Island. Besides all the maintenance releases we shipped some new features for lambdaisland.uri, our JS logging library Glögi, and a new micro-library, edn-lines. We also have some exciting work in progress, including a brand new browser-based test runner for ClojureScript, written with shadow-cljs in mind.

Funding

A big shout goes out to two of our clients, Nextjournal and Pitch. They have made a lot of this work possible either by funding projects directly, or by dogfooding our tools and libraries and giving us an opportunity to improve them. Thank you both for investing in this great ecosystem.

Coffee Grinders, part 2

Back in December I wrote about a coding pattern that I’ve been using more and more often in my work, which I dubbed “Coffee Grinders”. My thoughts around this were still gelling at the time, and so the result was a meandering semi-philosophical post that didn’t really get to the point, and that didn’t seem to resonate that much with people.

Some of the responses I got were “just use functions” or “sounds like a finite-state machine”, which makes it clear that I was not in fact making myself clear.

Having continued to encounter and apply this pattern I’d like to present a more concise, semi-formal definition of coffee grinders.

Launching an Open Collective for Lambda Island OSS

tl;dr

We are launching an Open Collective for Lambda Island Open Source, to help support our Open Source and Community work. Please check it out, pass it (and this article) on to your boss, or consider contributing yourself.

It started with a mission

Advent 2019 part 24, The Last Post

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

Day 24, I made it! I did skip a day because I was sick and decided it was more important to rest up, but I’m pretty happy with how far I got.

Let’s see how the others fared who took on the challenge. John Stevenson at Practicalli got four posts out spread out across the advent period, similar to lighting an extra candle every sunday of the advent. Good job!

Advent 2019 part 23, Full size SVG with Reagent

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

I’ve been a big fan of SVG since the early 2000’s. To me it’s one of the great

victories of web standards. Mind you, browser support has taken a long time to catch up.

Back then you had to embed your SVG file with an <object> tag, and support for the

many cool features and modules was limited and inconsistent.

These days of course you can drop an <svg> tag straight into your HTML. What a

joy! And since the SVG can now go straight into the DOM, you can draw your SVG

with React/Reagent. Now there’s a killer combo.

Advent 2019 part 21, Project level Emacs config with .dir-locals.el

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

An extremely useful Emacs feature which I learned about much too late is the

.dir-locals.el. It allows you to define variables which will then be set

whenever you open a file in the directory where .dir-locals.el is located (or

any subdirectory thereof).

Here’s an example of a .dir-locals.el file of a project I was poking at today.

Advent 2019 part 20, Life Hacks aka Emacs Ginger Tea

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

Here’s a great life hack, to peal ginger don’t use a knife, use a spoon. I’m not kidding. Just scrape off the peal with the tip of the spoon, it’s almost too easy.

Here’s a Clojure + Emacs life hack:

Advent 2019 part 19, Advent of Random Hacks

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

Something I’m pretty good at is coming up with random hacks. The thing where you’re like “hey how about we plug this thing into that thing” and everyone says “why would you do that that’s a terrible idea” and I’m like (mario voice) “let’s a go”.

And sometimes the result is not entirely useless. Like

this little oneliner

I came up with yesterday, using Babashka to “convert” a project.clj into a

deps.edn.

Advent 2019 part 18, Exploring Bootleg

Advent 2019 part 17, trace! and untrace!

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

Here’s a little REPL helper that you may like.

(defn trace! [v]

(let [m (meta v)

n (symbol (str (ns-name (:ns m))) (str (:name m)))

orig (:trace/orig m @v)]

(alter-var-root v (constantly (fn [& args]

(prn (cons n args))

(apply orig args))))

(alter-meta! v assoc :trace/orig orig)))

(defn untrace! [v]

(when-let [orig (:trace/orig (meta v))]

(alter-var-root v (constantly orig))

(alter-meta! v dissoc :trace/orig)))

Advent 2019 part 16, Coffee Grinders

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

Over the last year or so I’ve found myself using some variations on a certain pattern when modelling processes in Clojure. It’s kind of like a event loop, but adapted to the functional, immutable nature of Clojure. For lack of a better name I’m calling these coffee grinders. (The analogy doesn’t even really work but the kid needs to have a name.)

Since I saw Avdi Grimm’s OOPS Keynote at Keep Ruby Weird last year I’ve been thinking a lot about the transaction vs process dichotomy. Avdi talks about the “Transactional Fallacy” from around 15:25. From his slides:

Advent 2019 part 15, jcmd and jstack

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

Two shell commands anyone using JVM languages should be familiar with are jcmd

and jstack. They are probably already available on your system, as they come

bundled with the JDK. Try it out, run jcmd in a terminal.

This is what the result might look like

Advent 2019 part 14, Why did the Clojurist drop out of school?

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

Because they didn’t like classes.

Almost missed today’s post, so I’ll keep it short.

Advent 2019 part 13, Datomic Test Factories

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

When I started consulting for Nextjournal I helped them out a lot with tooling and testing. Their data model is fairly complex, which made it hard to do setup in tests. I created a factory based approach for them, which has served the team well ever since.

First some preliminaries. At Nextjournal we’re big fans of Datomic, and so naturally we have a Datomic connection as part of the Integrant system map.

Advent 2019 part 12, Pairing in the Cloud with Tmux

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

I’m a strong believer in pair programming. It can be intense and exhausting, and its a skill you need to learn and get good at, but it’s extremely valuable. It improves knowledge sharing, prevents mistakes, and helps people to stay on track to make sure they are building the right thing, which is arguably one of the hardest aspects of our job.

But Gaiwan is a remote-first company. We are spread out across Germany, Brazil, Italy, and work with clients as far away as Singapore and Hong Kong, so we need good ways to pair remotely. For this we need a tool that is

Advent 2019 part 11, Integrant in Practice

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

I’ve been a fan of Integrant pretty much ever since it came out. For me there is still nothing that can rival it.

The recently released clip by the folks from Juxt does deserve an honorable mention. It has an interesting alternative approach which some may prefer, but it does not resonate with me. I prefer my system configuration to be just data, rather than code wrapped in data.

Advent 2019 part 10, Hillcharts with Firebase and Shadow-cljs

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

Recently I led a workshop for a client to help them improve their development process, and we talked a lot about Shape Up, a book released by Basecamp earlier this year that talks about their process. You can read it for free on-line, and I can very much recommend doing so. It’s not a long read and there are a ton of good ideas in there.

One of these ideas has also become a feature in Basecamp, namely hill charts. These provide a great way to communicate what stage a piece of work is in. Are you still going uphill, figuring things out and discovering new work, or are you going downhill, where it’s mostly clear what things will look like, and you’re just executing what you discovered?

Advent 2019 part 9, Dynamic Vars in ClojureScript

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

Clojure has this great feature called Dynamic Vars, it lets you create variables

which can be dynamically bound, rather than lexically. Lexical (from Ancient

Greek λέξις (léxis) word) in this case means “according to how it is written”.

let bindings for instance are lexical.

(defn hello [x]

(str "hello " x))

(defn greetings []

(str "greetings" foo)) ;; *error*

(let [foo 123]

(hello foo)

(greetings))

Advent 2019 part 8, Everything is (not) a pipe

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

I’ve always been a big UNIX fan. I can hold my own in a shell script, and I really like the philosophy of simple tools working on a uniform IO abstraction. Uniform abstractions are a huge enabler in heterogenous systems. Just think of Uniform Resource Locators and Identifier (URLs/URIs), one of the cornerstones of the web as we know it.

Unfortunately since coming to Clojure I feel like I’ve lost of some of that power. I’m usually developing against a Clojure process running inside (or at least connected to) my trusty editor, and the terminal plays second fiddle. How do I pipe things into or out of that?

Advent 2019 part 7, Do that doto

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

doto is a bit of an oddball in the Clojure repertoire, because Clojure is a

functional language that emphasizes pure functions and immutabilty, and doto

only makes sense when dealing with side effects.

To recap, doto takes a value and a number of function or method call forms. It

executes each form, passing the value in as the first argument. At the end of

the ride it returns the original value.

Advent 2019 part 6, A small idiom

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

As an avid tea drinker I’ve been poring (pouring?) over this catalog of teas.

(def teas [{:name "Dongding"

:type :oolong}

{:name "Longjing"

:type :green}

{:name "Baozhong"

:type :oolong}

{:name "Taiwan no. 18"

:type :black}

{:name "Dayuling"

:type :oolong}

{:name "Biluochun"

:type :green}])

Advent 2019 part 5, Clojure in the shell

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

I already showed you netcat, and how it combines perfectly with socket REPLs. But what if all you have is an nREPL connection? Then you use rep

$ rep '(clojure.tools.namespace.repl/refresh)'

:reloading ()

:ok

Advent 2019 part 4, A useful idiom

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

Here’s a little Clojure idiom that never fails to bring me joy.

(into {} (map (juxt key val)) m)

Advent 2019 part 3, `every-pred` and `some-fn`

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

Ah clojure.core, it’s like an all you can eat hot-pot. Just when you think

you’ve scooped up all it has to offer, you discover another small but delicious

delicacy floating in the spicy broth.

In exactly the same way I recently became aware of two functions that until now had only existed on the periphery of my awareness. I’ve since enjoyed using them on several occasions, and keep finding uses for them.

Advent 2019 part 2, Piping hot network sockets with Netcat

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

Part of what I want to do in this series is simply point at some of the useful tools and libraries I discovered in the past year. I’ve adopted a few tools for doing network stuff on the command line which I’ll show you in another post. First though we’ll look at a classic: netcat!

I’ve been using netcat for years, it’s such a great tool. It simply sets up a TCP connection and connects it to STDIN/STDOUT. Pretty straightforward. I’ve been using it more and more though because of Clojure’s socket REPL.

Advent 2019 part 1, Clojure Vocab: to Reify

This post is part of Advent of Parens 2019, my attempt to publish one blog post a day during the 24 days of the advent.

An interesting aspect of the Clojure community, for better or for worse, is that it forms a kind of linguistic bubble. We use certain words that aren’t particularly common in daily speech, like “accretion”, or use innocuous little words to refer to something very specific. Even a simple word like “simple” is no longer that simple.

We can thank Rich Hickey for this. He seems to care a great deal about language, and is very careful in picking the words he uses in his code, documentation, and in his talks.

Advent of Parens 2019

Ah, the advent, the four weeks leading up to Christmas. That period of glühwein and office year-end parties.

The last couple of years I’ve taken part in the Advent of Code, a series of programming puzzles posted daily. They’re generally fun to do and wrapped in a nice narrative. They also as the days progress start taking up way too much of my time, so this year I won’t be partaking in Advent of Code, instead I’m trying something new.

From the first to the 24th of December I challenge myself to write a single small blog post every day. If my friend Sarah Mirk can do a daily zine for a whole year, surely I can muster a few daily paragraphs for four weeks.

Lambda Island Streaming Live this Thursday and Friday

We are definitely back from holidays, and to demonstrate that we’re not just doing one but two live stream events!

Felipe and Arne pairing

Thursday 5 September, 13:00 to 15:00 UTC

Fork This Conference

Last weekend Heart of Clojure took place in Leuven, Belgium. As one of the core organizers it was extremely gratifying to see this event come to life. We started with a vision of a particular type of event we wanted to create, and I feel like we delivered on all fronts.

For an impression of what it was like you can check out Malwine’s comic summary, or Manuel’s blog post.

It seems people had a good time, and a lot of people are already asking about the next edition. However we don’t intend to make this a yearly recurring conference. We might be back in two years, maybe with another Heart of Clojure, maybe with something else. We need to think about that.

Advice to My Younger Self

When I was 16 I was visited by a man who said he had come from the future. He had traveled twenty years back to 1999 to sit down with me and have a chat.

We talked for an hour or so, and in the end he gave me a few pieces of advice. I have lived by these and they have served me well, and now I dispense this advice to you.

Become allergic to The Churn

ClojureScript logging with goog.log

This post explores goog.log, and builds an idiomatic ClojureScript

wrapper, with support for cljs-devtools,

cross-platform logging (by being API-compatible with Pedestal Log), and logging

in production.

This deep dive into GCL’s logging functionality was inspired by work done with Nextjournal, whose support greatly helped in putting this library together.

Clojure’s standard library isn’t as “batteries included” as, say, Python. This is because Clojure and ClojureScript are hosted languages. They rely on a host platform to provide the lower level runtime functionality, which also allows them to tap into the host language’s standard library and ecosystem. That’s your batteries right there.

Test Wars: A New Hope

Yesterday was the first day for me on a new job, thanks to Clojurists Together I will be able to dedicate the coming three months to improving Kaocha, a next generation test runner for Clojure.

A number of projects applied for grants this quarter, some much more established than Kaocha. Clojurists Together has been asking people through their surveys if it would be cool to also fund “speculative” projects, and it seems people agreed.

I am extremely grateful for this opportunity. I hope to demonstrate in the coming months that Kaocha holds a lot of potential, and to deliver some of that potential in the form of a tool people love to use.

Two Years of Lambda Island, A Healthy Pace and Things to Come

It’s been just over two years since Lambda Island first launched, and just like last year I’d like to give you all an update about what’s been happening, where we are, and where things are going.

To recap: the first year was rough. I’d been self-employed for nearly a decade, but I’d always done stable contracting work, which provided a steady stream of income, and made it easy for me to unplug at the end of the day.

Lambda Island was, as the Dutch expression goes, “a different pair of sleeves”. I really underestimated what switching to a one-man product business in a niche market would mean, and within months I was struggling with symptoms of burnout, so most of year one was characterised by trying to keep things going and stay afloat financially, while looking after myself and trying to get back to a good place, physically and mentally.

D3 and ClojureScript

This is a guest post by Joanne Cheng (twitter), a freelance software engineer and visualization consultant based in Denver, Colorado. She has taught workshops and spoken at conferences about visualizing data with D3. Turns out ClojureScript and D3 are a great fit, in this post she’ll show you how to create your own visualization using the power of D3 and the elegance of ClojureScript.